Mapping Natural Resource Priorities

The title is a bit of a mouthful, but the concept is fairly straightforward: gather a bunch of experts and ask them to talk about the natural resources in their community. If you structure the process correctly, the results can tell you which natural resources provide the greatest ecosystem services, which are threatened by planned development and even give a reflection of a community’s identity. In my work at the Delta Institute, I have done a lot of work around environmental valuation, especially as it pertains to our environments’ ability to provide services to humans, but I have honed in on a couple of specific areas, one of which is putting a community’s natural resource prioritize in a geographic context.

Transportation and Environmental Collaboration

One such project was Delta’s Transportation & Environmental Collaboration project, completed in 2012. The primary aim of the project was to bridge the gap between 1) local environmental groups concerned with conservation of natural areas and 2) transportation agencies tasked with building new infrastructure. From the official project description:

The Delta Institute is facilitating a Transportation and Environmental Collaboration Initiative in McHenry County, IL (working with local partners McHenry County Defenders and The Land Conservancy of McHenry County) and in Northwest Indiana (working with local partners Shirley Heinz Land Trust and Save the Dunes). The primary goal of the Initiative is to strengthen relationships between environmentalists and transportation professionals to ensure a balanced and informed dialogue with both groups. To achieve the goal of strengthening relationships in the first year of the project, Delta convened local stakeholder groups of environmentalists, hosted workshops and created a consensus-driven prioritization map of natural resources. In year two, Delta will help the McHenry and Northwest Indiana groups refine the prioritization map and implement an outreach plan for the prioritization map. Delta will also facilitate a series of webinars in Winter and Spring 2012 to build capacity throughout the region on transportation and environmental topics.

My role began in Year 2 and I was responsible for finalizing the priority resource maps for each of the project areas, building and implementing a series of webinars and working with project partners to take the project’s collected knowledge and develop easily digestible outreach materials.

Finalizing the map

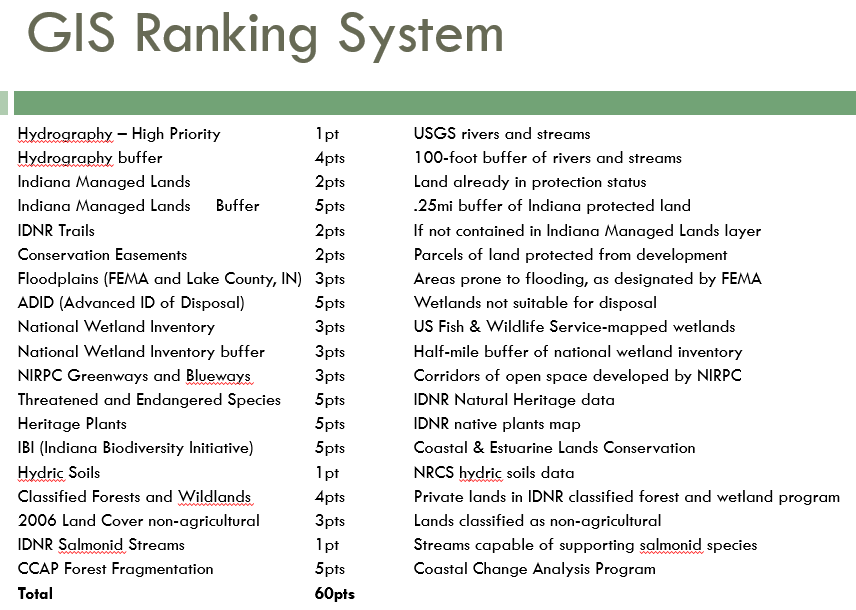

In Year 1, Delta worked with local GIS agencies to collect natural resource data and build maps showing weighted natural resource values across each respective project area. The resulting maps were interesting, but had two problems we needed to overcome:

- While the maps captured large-scale resources, there were still some gaps in local knowledge

- They were fairly difficult to put into context, especially for people outside of the project

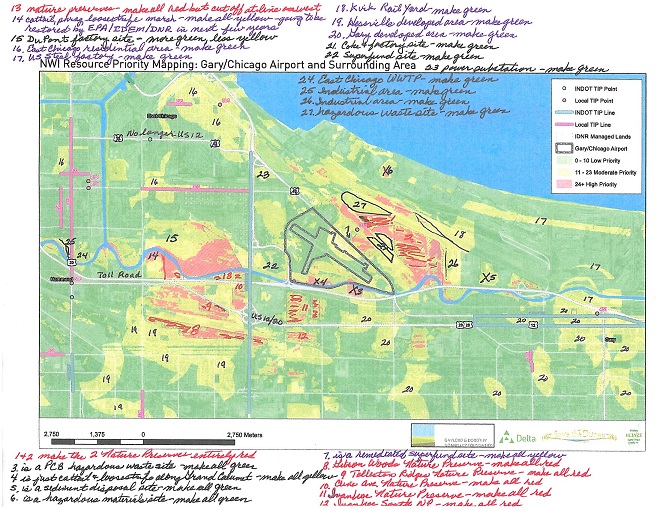

To address problem 1, we distributed paper maps to our natural resource experts and asked them to fill in any missing information, along with notation on how we might acquire the correct data. The results were surprisingly detailed and demonstrated that the data we rely on every day isn’t always as complete as we’d like to believe.

To address problem 2, we developed 11x17” ‘site narratives’ for each of the high-risk areas identified by our stakeholder groups. This process helped put the massive and complex datasets into a more understandable framework - where do threats exist (in this case, planned transportation projects), how might those threats impact high-value natural areas and what can be done to ameliorate those threats? The final products were still a bit complex, but offered a platform from which to talk about the intersection of transportation projects and natural areas.

Connecting groups and community values

Our partners agreed that the mapping process helped shine a spotlight on some key areas they hadn’t previously identified, but, in my assessment, the project’s greatest value was in convening two disparate groups (environmentalists and transportation professionals) with surprisingly common goals.

One early lesson from the project was that environmentalists often bring up their concerns far too late in the project planning process. The easy (and possibly cynical) explanation is that transportation agencies purposefully hide the process from public view in order to avoid inconvenient objections. However, the transportation professionals who participated in our process were happy to point environmental groups to long-term planning documents, explain how to get involved early on in the process and even asked for guidance on how to better identify environmental risks before they become a problem.

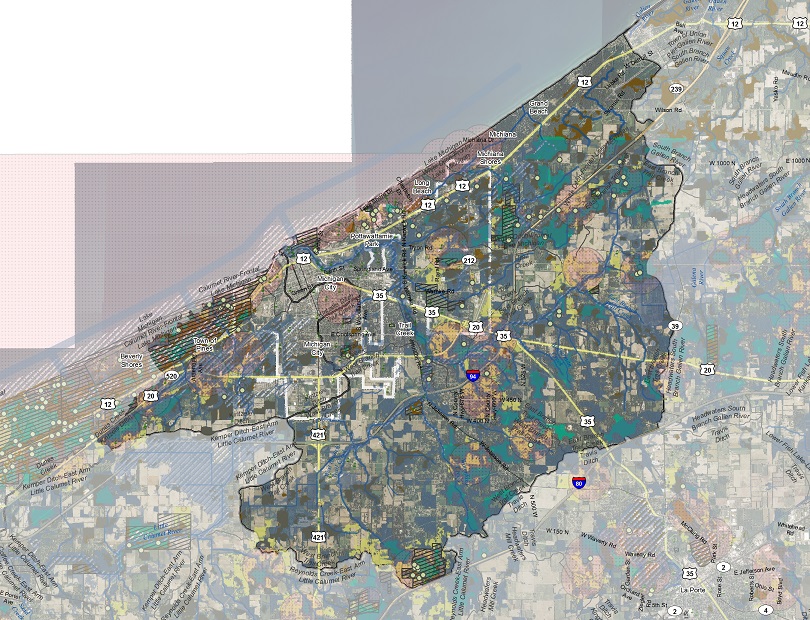

Climate Adaptation and Land Conservation Policy in Michigan City

Delta built on its success in the previous project by branching out to Michigan City, Indiana. The aim of the Michigan City work is once again to identify, prioritize and plan around natural resources, but adds a couple of unique twists. First, the primary project partner is the Michigan City Sanitary District (MCSAN), a regulated waste water and storm water treatment facility. Second, the project team was able to secured additional funding to develop a long-term land use policy to ensure natural resources are prioritized in the long-term. And finally, the process is explicitly focused on planning for the effects of climate change.

Tweaking the process

Much like the prioritization project in Northwest Indiana and McHenry County, this process involved collecting and ranking a wide range of geospatial data. However, for this project we opted to capture as much local knowledge as early as possible. We used a few different strategies to capture local knowledge, but our stakeholders’ favorite was something we called the ‘big map exercise,’ which is exactly what it sounds like. I developed an enormous map (12 feet x 12 feet at 300 dpi resolution), printed it on a plotter in strips and assembled it on a huge table. Participants crawled around on the map and placed coded stickers where the wanted to make an edit. Once a sticker was placed, they would then fill out a matching coded form with detailed information.

I took the map back to our office, trued up the comment stickers with their respective forms and set about digitizing the whole thing by laying it out on the floor and taking a crude approximation of aerial photographs using a digital camera (complete with my socks). I then traced the stakeholder edits and integrated them into the list of priority natural areas.

Taking it to the next step - implementing policy

As a final step (currently in process), we are working with our local partners in Michigan City to design a policy or set of policies to institutionalize land use strategies for both conserving natural resources and also integrating climate change adaptation into the land use decision-making process. Once a policy has been designed and implemented, we will help fund two on-the-ground conservation and/or green infrastructure projects to demonstrate the value of and process for utilizing the new policy.

Future process tweaks

In the future, I would like to develop a new method for collecting local knowledge that doesn’t rely on paper map handouts or giant floor maps (no matter how fun they may be). I believe people have a difficult time putting local features into geographic context, especially if that context is significantly larger than the local features in question. There is tremendous potential to leverage the huge body of knowledge and experience in the OpenStreetMap community, especially since the advent of the new, beginner-friendly iD editor (which has been forked for some pretty slick projects). There are also some tremendous new tutorials coming out of the Maptime community, which, incidentally, I am helping to coordinate in Chicago.